I first read Young Goodman Brown in high school and recall being puzzled by it. Hawthorne’s prose was perhaps a bit too dense for me, as I suspect it was for most of my ninth grade English class. But there was something unsettling about it, and I returned to it again and again through the years. Eventually, Hawthorne became one of my favorite writers, but it was an acquired taste.

We’re in the Puritan village of Salem; the tale was written in 1835 but Hawthorne is reaching back to the witch trials of 1692-93. The story seems straightforward. Young Goodman Brown leaves his wife, Faith, to go out on some ‘evil purpose,’ against her wishes. He travels past the town meeting house in Salem Village, and Hawthorne sets a foreboding tone:

“It was all as lonely as could be; and there is this peculiarity in such a solitude, that the traveller knows not who may be concealed by the innumerable trunks and the thick boughs overhead; so that, with lonely footsteps, he may yet be passing through an unseen multitude.”

“What if the devil himself should be at my very elbow!” Brown remarks, as he continues on his way. He meets others from the village on his path, including a man who is older than him, around age fifty, but who looks just like him, and remarks in a very matter of fact way that he had done terrible things with Young Goodman Brown’s grandfather:

“I helped your grandfather, the constable, when he lashed the Quaker woman so smartly through the streets of Salem. And it was I that brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village, in King Philip’s War. They were my good friends, both; and many a pleasant walk have we had along this path, and returned merrily after midnight. I would fain be friends with you, for their sake.” The stranger goes on to say that he is acquainted will the deacon, the governor, and other elders of the town. This shakes Brown’s understanding of his own family and village, leaving him quite unsettled.

This stunning section ramps up the tension until Brown hears the voice of his wife, Faith, and is distraught that she is in the woods. He arrives at a clearing where all the village is assembled; he and Faith are to be initiated in a ceremony, binding them to the devil. He calls out to Faith that she must resist and “look up to heaven,” at which point the villagers disappear.

Brown is unsure whether the entire story was a dream, but it bewilders him to the point that “A stern, a sad, a darkly meditative, a distrustful, if not a desperate man, did he become, from the night of that fearful dream.” Hawthorne’s final sentence is: “And when he had lived long, and was borne to his grave, a hoary corpse, followed by Faith, an aged woman, and children and grand-children, a goodly procession, besides neighbors, not a few, they carved no hopeful verse upon his tombstone; for his dying hour was gloom.”

It may not be entirely fashionable today to believe in good and evil or supernatural powers, but this story still leaves me unsettled. The idea that your friends and neighbors, or your entire conception of the world, may be totally wrong, is something no one wants to admit. But the devil is right there in the story, cheerfully informing Brown that his father committed atrocities, that his grandfather enthusiastically persecuted his neighbors, and that Brown himself is on friendly terms with evil. Everyone in Salem is implicated; the story takes place during the Witch trials, at which Hawthorne’s own grandfather was a judge, making this tale even more grim.

There are no easy interpretations or answers in this tale. Brown lives the rest of his days haunted by his knowledge. There’s no redemption for him from God, or from anyone else, even his beloved Faith.

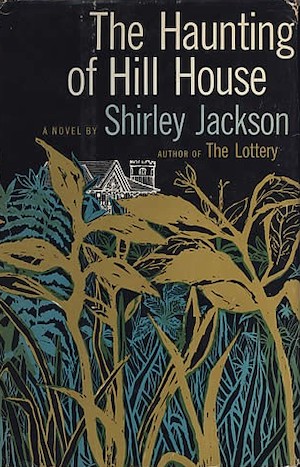

Hawthorne wrote plenty more in this vein: A Scarlet Letter, The House of Seven Gables, and numerous stories, and all of them leave me with this same feeling of helplessness in the face of evil. They’re also incredible to read, with the stylized, romantic prose adding to the sense of gloom and mystery.

I am not sure of Hawthorne is still taught in high schools, but he ought to be. This is one of the best short stories you’ll ever read, one that has stayed with me in the three and a half decades since I first encountered it.