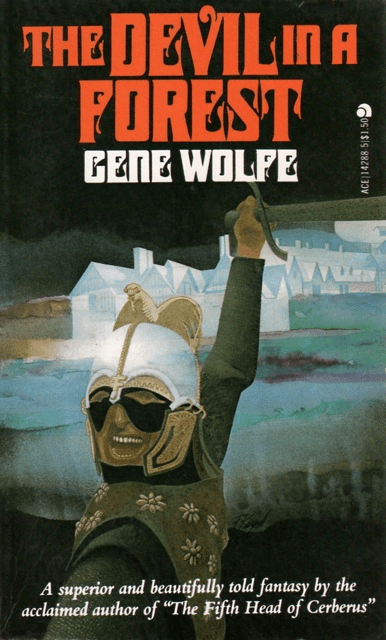

Gene Wolfe is one of my favorite writers, and this is a wonderful book of his that I found some years after reading his epic Book of the New Sun, an amazing series that I want to reread soon. Unlike that dense, lengthy work, this is a shorter novel of mystery, adventure and myth, but like Wolfe’s other novels, it is beautifully written, tightly plotted and great fun to read. I just re-read it over the holidays, after hearing the carol, ‘Good King Wenceslas,’ which reminded me of the book. Wolfe explains his writing inspiration for this novel in the epilogue:

“Shortly before Christmas one year, Gene Wolfe was singing the carol ‘Good King Wenceslas’ and was struck by the king’s questions to his page: “Yonder peasant, who is he? Where, and what his dwelling?” And by the page’s answer: “Sire, he lives a good league hence, Underneath the mountain, Close against the forest fence, By St. Agnes’ fountain.”

Wolfe recalls, “I found myself wondering who, indeed, was that nameless medieval peasant from whom most of us are, in one way or another, descended.”

The Devil in a Forest is Wolfe’s story surrounding this peasant, whose little village becomes involved in a struggle between a nameless evil and the forces of good. There is a dangerous highwayman, a mysterious murder, and strange powers that converge upon this village and create havoc for Mark, the protagonist. The attention to detail in Mark’s day to day life, and that of his fellow villagers, is quite well done and made for some interesting reading. Mark’s trials and his battle for survival are suspenseful, keeping you guessing right until the end. I enjoyed this one very much—it is so different from some of Wolfe’s other books, but his concept and the execution are excellent. I don’t want to spoil the fun for those who may be interested in reading this one, but I recommend it to anyone who has enjoyed Wolfe’s more well-known books. Fantasy writing doesn’t get much better.